Contenus de la page

ToggleHow to read a scientific paper

As part of your research work, you will be required to read numerous scientific articles and journals, which are more generally called scientific papers or papers.

There literature growing very quickly, you need to have the right eye to identify the most relevant articles for your research (see the previous course).

There is research discussing how to perform a scientific paper reading. In this course, we will present the techniques that have proven themselves and are recommended by the scientific community.

S.Keshav's three passes and Pomodoro session

In order to read a scientific paper optimally (i.e. first and foremost to know if the content will be relevant to you), S.Keshav suggests reading the paper three times, each time with a different objective.

- First pass: Bird's eye view

- Second pass: Enter content

- Third pass: Understanding the content

Before tackling the three steps, we offer you various techniques to avoid demotivation and procrastination (the state of the art can have the effect of a blank page even for the most experienced).

The Pomodoro technique is a great tool if you lack motivation.

Take a timer and set it for 25 minutes. Don't expect any result. Eliminate all distractions and follow the three-pass approach until the 25 minutes are up.

By using this siloing approach, you will put all your energy in the right direction and gain more knowledge and information when multitasking. The good thing is that you can apply the Pomodoro technique to any task.

First pass: bird's eye view

The goal of the first pass is to get an overview of the scientific paper and should take no more than 10 minutes. You don't need to go into detail or even read the entire document.

The first pass consists of hovering over the Article Structure, reading the Title, the Abstract and the Conclusion, and hover over the Introduction.

You must be able to answer the questions following:

Category : The category describes the type of paper. Is this article about a prototype? About a news method optimization? Is this a literary investigation?

Context : The context puts the article in perspective with other articles. What other papers are related to this one? Can you connect it to anything else? You can also view context as a TREE semantics in which you assign specific importance to the document. Is it an important branch or an uninteresting leaf? Maybe you have no prior knowledge in this area and therefore still need to build your semantic tree from scratch. It can be demotivating at first but that's normal. (See the Mind Map and Concept Map course).

Exactness : Accuracy is, as the name suggests, a measure of validity. Are the assumptions valid? Most of the time the first pass won't give you enough information to answer this question with certainty, but you probably have a hunch that is sufficient at first.

Contributions: Most articles have a list of their contributions directly in the introduction section. Are these contributions significant? Are they useful? What problems do they solve? Are these contributions new?

Clarity: Based on the sections you have just read, do you think the document is well written? Did you spot any grammatical errors? Typos?

Is it worth reading further?

This pass should serve as a quick first filter. When you have completed the first pass, you may decide to read further and continue with the second pass or you decide not to read further because:

- You lack general information

- You don't know enough about this topic

- The paper doesn't interest or benefit you

- The paper is poorly written

- The authors make false assumptions

If this article is not in your area of expertise but may become relevant to you later, this first pass is sufficient and you probably do not need to continue reading. If not, you can continue with the second pass.

Second pass: enter the content

The second pass can last up to 1 hour and here you should read the entire scientific paper. Ignore details like proofs or equations, because most of the time you won't need this specific knowledge anyway and it will cost you valuable time.

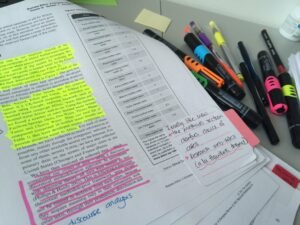

Writing small summaries or key points in the margins in your own words is a great way to see if you really understand what you've just read; and you will remember it much longer.

Using the second pass, you can enrich your Concept Map or Mind Map or simply cross-reference and correct the information already present (see the Concept Map and Mind Map course).

At the end of the second passage, you may still not understand what you have just read. This could be due to many reasons. Maybe it's not your area of expertise or you lack basic information.

You can already mark relevant unread references for further reading, which is a good way to learn more about the context.

→ You can stop reading further because the paper is not beneficial to you for several reasons

→ Put the paper aside and continue reading after reading some reference materials

→ Continue with the third pass

Third pass: understanding the content

If you're a beginner, this pass probably takes 4-5 hours. It's a lot of work and you should carefully consider whether this step is worth your time.

This step is mandatory if you are a designated reviewer of the scientific paper or if you already know for sure that you need to understand the document in all its details.

Read the entire scientific paper and question every detail. Now it's time to get into the math equations and try to figure out what's going on. Make the same assumptions as the authors and recreate the work from scratch.

Whether you make a Mind Map, Concept Map or a reading sheet, we invite you to go back to the root of this course in order to head to the dedicated courses.

Feynman method

After reading several scientific papers, it is important to extract the essential information. The state of the art requires a capacity for abstraction and advanced knowledge in order to understand its entirety. problematic and work already carried out. For this, it is possible to use the Feynman method.

Write down everything you know about the subject. Whenever you come across new sources of information, add them to the note.

Ex. An optimization method → A metaheuristic → Swarm optimization → Ant colony

The use of the ant colony in energy optimization (microgrid)

This is the time when real learning happens. What are you missing? What don't you know? What do you need to complete your slides?

Ex. An optimization method (def. decision making) → A metaheuristic (among what?) → Swarm optimization → Ant colony (which ? How to compare them?)

The use of the ant colony in energy optimization (microgrid).

Other similar items and the difference in settings? Paper with swarm optimization?

Start telling your story. Collect your notes and start telling a story using concise explanations. Gather the most essential elements of your knowledge on the subject.

Creating a good presentation is like a puzzle.

Use analogies and simple sentences to reinforce your understanding of the story.

“All things are made of atoms – small particles that move in perpetual motion, attracting each other when they are a small distance apart, but repelling each other when they are close together against others. »

It is important to learn how to write the Introduction and the State of the Art before continuing his research and starting the Methodology.